Using Science to Break the Serious Long-Term Health Implications of Childhood Trauma

By Stephanie Jordan

By Stephanie Jordan

Managing Editor, Connections

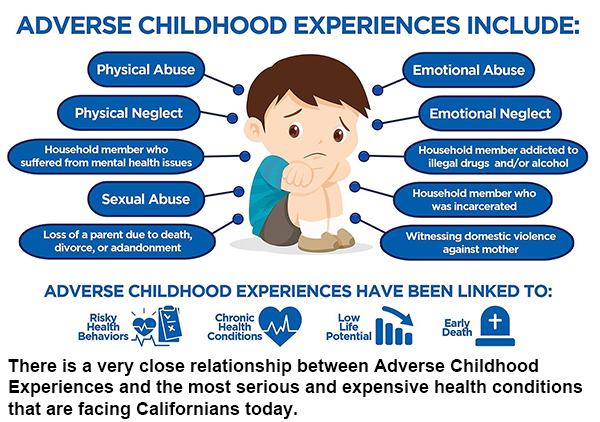

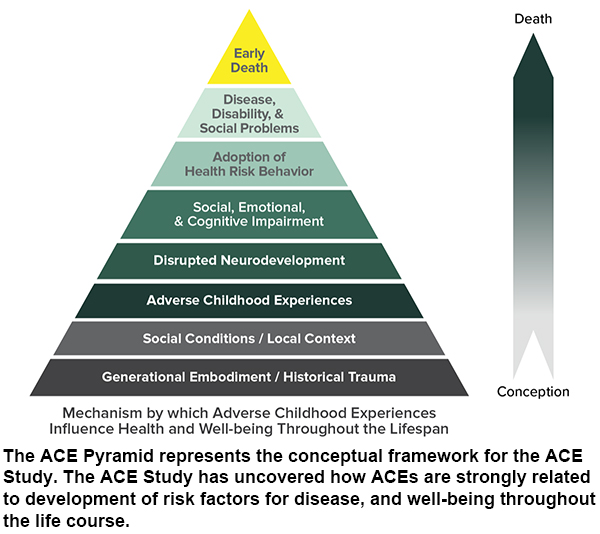

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress represent a public health crisis that has been, until recently, largely unrecognized by the health care system and society. ACEs are stressful or traumatic events experienced prior to age 18. A consensus of scientific research demonstrates that cumulative adversity, especially when experienced during critical periods of early development, is a root cause to some of the most harmful, persistent, and expensive health challenges facing California and the nation.

Toxic Stress and Immune Systems

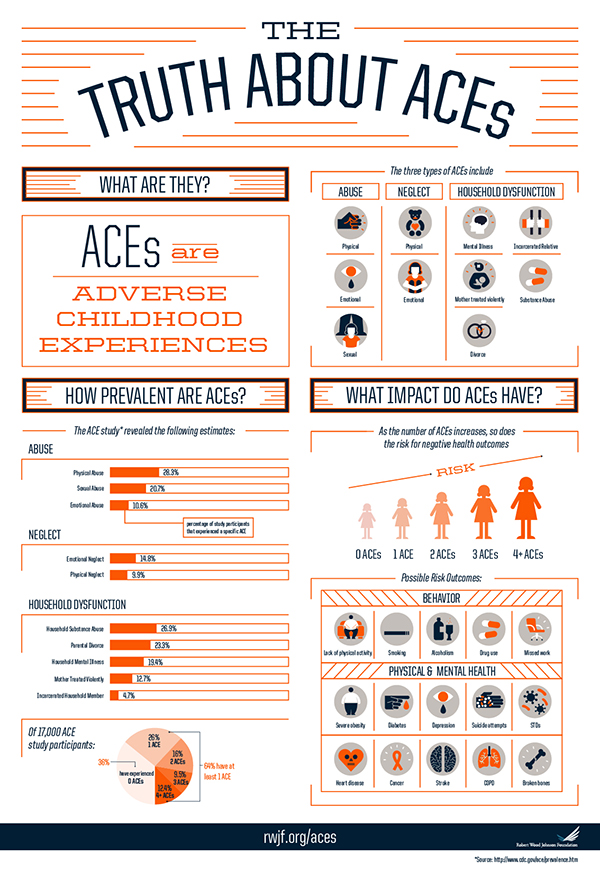

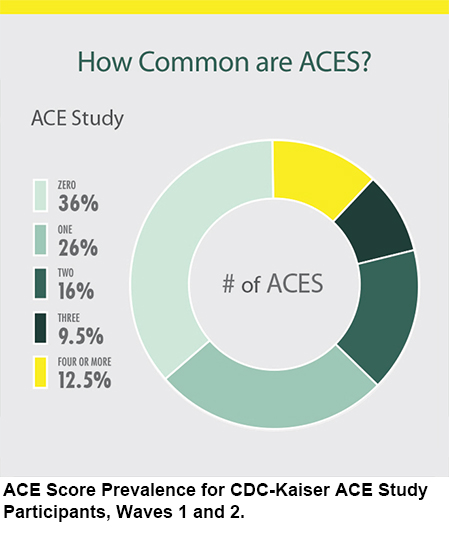

A landmark study, published in 1998 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente on adverse childhood trauma was described by the CDC as “one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect and later-life health and well-being.” That study, conducted between 1995 and 1997 revealed that there was a strong correlation between a child’s exposure to traumatic experiences and their likelihood of developing certain diseases in adulthood. The study specified 10 categories of stressful or traumatic childhood events, including abuse, parental incarceration, and divorce or parental separation; its research showed that sustained stress caused biochemical changes in the brain and body and drastically increased the risk of developing health problems and mental illness.

“Anecdotally we [practitioners] have known, but it’s only been in the past five years or so that ACEs has really come into the forefront of our medical awareness; before then it was more commonly an issue for a social worker,” explains Dr. Alice Jacobs Vestergaard, a faculty member in the School of Nursing at Samuel Merritt University. Vestergaard is an internationally published author, educator, and researcher who has over two decades of experience working with multicultural, multilingual, and multigenerational populations in diverse community settings. She has had careers in both industry and higher education, and has lived and worked in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres serving marginalized populations

Why has it taken so long to identify ACEs as a long-term health risk?

Why has it taken so long to identify ACEs as a long-term health risk?

“We have the science now; we didn’t have that before,” says Wendie Lee Skala, RN, BSN, MS, who works closely with colleague Vestergaard as Adjunct Faculty in community health at Samuel Merritt’s School of Nursing and spreads the word about ACEs and Resiliency through her work with Resilient Sacramento, an ACEs Connection Collaborative. “With an MRI we can actually see brain changes and predict when a child may have trouble accessing the cerebral cortex.”

Early in her career, Skala specialized in intensive care and emergency nursing with emphasis on cardiovascular disease. Skala flew for Stanford Life Flight for 10 years and honed her skills in prehospital transport of critically injured patients. She joined the Air Force Reserve in 1999 achieving the rank of Lt. Col. while serving in support of OPERATION IRAQI AND ENDURING FREEDOM transporting wounded warriors.

Skala deepened her experience with ACEs, when in 2009 she took on the role as the Injury Prevention Coordinator for Kaiser Permanente’s first trauma center in South Sacramento. There she implemented the Sacramento Violence Intervention Program that provided services for shot, stabbed, and almost assaulted to death victims of violence between the ages of 15 and 26. In her role at Kaiser Permanente, Skala worked with law enforcement, schools, non-profits, and government agencies to educate about ACEs and Trauma Informed Care. She has presented nationally on the subject and is a contributing author and educator of the American Trauma Society’s Injury Prevention Course.

To help explain the state of mind of a child with ACEs, Skala tells the story of a bear in the forest. “If you are walking in a forest and you come across a bear, your flight or fight response kicks in, the amygdala, an area of the brain that contributes to emotional processing, sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus. This area of the brain functions like a command center, communicating with the rest of the body through the nervous system so that the person has the energy to fight or flee. What happens when the bear comes home every night? The child is bathed in the stress hormones.” Children are especially vulnerable to this stress response because their brains and immune systems are still developing.

Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, was one of the first scientists to take the anecdotal claims about the benefits of meditation and mindfulness and test them in brain scans. The first study (2005) looked at long-term meditators vs. a control group.

“We found long-term meditators have an increased amount of gray matter in the insula and sensory regions, the auditory and sensory cortex,” reveals Lazar. “Which makes sense. When you’re mindful, you’re paying attention to your breathing, to sounds, to the present moment experience, and shutting cognition down. It stands to reason your senses would be enhanced.”

So Lazar conducted a second study (2011) with people who’d never meditated before, and put one group through an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Reports Lazar:

“We found differences in brain volume after eight weeks in five different regions in the brains of the two groups. In the group that learned meditation, we found thickening in four regions: 1. The primary difference, we found in the posterior cingulate, which is involved in mind wandering, and self relevance. 2. The left hippocampus, which assists in learning, cognition, memory and emotional regulation. 3. The temporo parietal junction, or TPJ, which is associated with perspective taking, empathy and compassion. 4. An area of the brain stem called the Pons, where a lot of regulatory neurotransmitters are produced. The amygdala, the fight or flight part of the brain, which is important for anxiety, fear and stress in general got smaller in the group that went through the mindfulness-based stress reduction program.”

Spreading awareness that ACEs harm children's developing brains and lead to changing how they respond to stress and damage kids immune systems so profoundly that the effects show up decades later causing a burden of chronic disease, most mental illness, and are at the root of most violence, is a priority for both Skala and Vestergaard.

“With the recognition that more and more health care is moving to community based models with a prevention focus versus acute care settings, knowledge and information regarding ACEs takes on increased significance and relevance,” believes Vestergaard. “Health care personnel across the entire health care landscape must know and understand how to screen for ACEs and then provide assistance to patients to either help patients directly or assist patients to find the resources needed to promote resiliency. This may require an interdisciplinary approach and also awareness of community resources to assist patients.”

Vestergaard has developed unique community clinical collaborations that entail placing nurses working in acute care settings who are returning to school to earn BSN degrees, into community agencies with highly ACEs impacted clients.

Vestergaard explains, “Partnering with the county library system, agencies serving homeless and housing insufficient clients, community groups serving targeted ethnic populations, and low income elderly living in HUD housing, provides the acute care-based nurse, a lens into the social determinants of health and the impact of ACES across the lifespan.”

High-Powered Help

High-Powered Help

For ACEs awareness advocates like Skala and Vestergaard, Governor Gavin Newsom provided a strong ally in Dr. Nadine Burke Harris when he created the role of California’s first Surgeon General in January of 2019 to serve as a leading spokesperson on matters of public health, and drive solutions to California’s most pressing public health challenges. Burke Harris has established early childhood, health equity, and ACEs and toxic stress as key priorities; setting a bold goal to reduce ACEs and toxic stress by half in one generation.

"When we are talking about addressing the root cause, science shows that safe, stable environments are healing for kids," said Burke Harris, who is also the author of The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity. "This involves public education, routine screening to enable early detection and early intervention, and cross-sector coordinated care," she said at a hearing on providing care in schools held by the House Committee on Education and Labor in September. "The opportunity ahead of us is about a true intersection of health care and education."

Training providers how to screen for ACEs is behind the ACEs Aware initiative that Burke Harris and Dr. Karen Mark, Medical Director at the state Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), unveiled in December. Phase one of the initiative is a first-of-its-kind statewide effort to offer provider training to screen pediatric and adult patients for 10 categories of ACEs, which include abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. The two-hour online curriculum will be easy to access for a wide range of health care professionals and will provide continuing medical education (CME) and maintenance of certification (MOC) credits. This training is available to all providers.

As of January 1, through the ACEs Aware initiative, Medi-Cal providers can receive training, clinical protocols, additional resources, as well as payment for screening children and adults for ACEs.

“The ACEs Aware initiative is harnessing and building upon the momentum and expertise that has been growing in the scientific community for more than a decade,” said Burke Harris during the initiative’s unveiling with nearly 1,000 providers and health leaders from throughout California participating in the online event.

The curriculum and provider training is now available at ACEsAware.org. The reason the initiative is a focus for the Governor and Surgeon General is because according to the most recent California Department of Public Health data reporting from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS, 2017), 63.5 percent of Californians have experienced at least one of the ACEs, and 17.6 percent of Californians have experienced four or more. Nationally, the prevalence rate is similar.

In an interview with her alma mater, U.C. Davis, Burke Harris explained why the ACEs numbers are of concern. “What we see is that there’s a really close relationship between ACEs and the most serious and expensive health conditions that are facing Californians today. That’s 17.6 percent of Californians who see twice the risk of heart disease, more than twice the risk of cancer, two and a half times the risk of stroke, triple the risk of chronic lung disease, four and a half times the risk of depression, and 30 times the risk of suicide. We also see six times the risk of incarceration, and double the risk of asthma in children. It’s a big deal — this is the definition of a public health crisis.”

Funding for the ACEs Aware initiative comes from Proposition 56 and is part of Governor’s “California for All” initiative, which aims to improve health and bolster early interventions for the state’s youngest Californians. The 2019-20 state budget provides $40.8 million to DHCS for ACEs screenings for children and adults enrolled in Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program. As of July 1, 2020, Medi-Cal providers must have taken a certified training and self-attested to completing the training to receive Medi-Cal reimbursement for ACE screenings.

ACEs Connection

ACEs Connection

Skala hopes that the ACEs Aware initiative is well received and that more providers get on board to support ACEs screening.

The state has influence over Medi-Cal so the December announcement makes sense,” reasons Skala. “It is wonderful to have the Surgeon General focusing on ACEs. She is a very dynamic and speaks to the subject so well. She has been shouting from the rooftop and travelling all over the world to speak about it.”

An excellent resource that support’s Burke Harris’ mission that Skala has been involved with since its launch in 2012 is ACEs Connection, which is comprised of the social network ACEsConnection.com and the news site ACEsTooHigh.com. Founder and publisher Jane Ellen Stevens’ sites supports local ACEs initiatives in neighborhoods, cities, counties, states and nations. The community-based site is full of free materials and guidelines on how to launch and grow local ACEs initiatives, gain access to powerful online tools that help initiatives measure progress, and hosts interest-based communities.

Resources like ACEs Connection are vital to building awareness and sharing ideas about how best to leverage a community’s ideas, successes, and challenges to make significant progress using ACEs science. As more people understand the circumstances of a young person that on the surface appears to be “difficult” or “acting out”, the more the individual can be helped.

The effect of an adult can make a big difference to a young person’s circumstances,” says Vestergaard. “Just ONE caring, loving adult advocating for them – a teacher, parent, or neighbor can make the world of difference. We can teach kids how to self-regulate when triggered and help them learn how to self-soothe. But first we have to understand the brain science and how toxic stress caused by ACEs affects behavior as well as short- and long-term health.

What’s Your ACEs Score?

What’s Your ACEs Score?

The level of understanding, believes Vestergaard and Skala, can only be enhanced if every practitioner can see the world through an ACEs-science-informed lens. Both encourage health care professionals to screen themselves to see how ACEs might be present in their own lives.

“In the original 1998 CDC and Kaiser Permanente study in San Diego, the majority of participants were white upper middle class, college educated with jobs and 64 percent had at least one ACE,” points out Skala. “It is not only about those people over there, it is about all of us. There is one ACE in particular that can result in a child experiencing eight additional ACEs. That particular ACE is having a parent who abuses or is addicted to alcohol or other drugs. At conferences when asked: how many of us have experienced addiction, or a family member with addiction, or emotional neglect, or mental illness, or incarceration, or abuse, etc. to please stand, pretty soon the whole room is on its feet.”

There are 10 types of childhood trauma measured in the ACE screening. Five are personal — physical abuse, verbal abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. Five are related to other family members: a parent who’s an alcoholic, a mother who’s a victim of domestic violence, a family member in jail, a family member diagnosed with a mental illness, and the disappearance of a parent through divorce, death or abandonment. Each type of trauma counts as one.

The most important thing to remember is that the ACE score is meant as a guideline: If someone experienced other types of toxic stress over months or years, then those would likely increase the risk of health consequences. As an ACE score increases, so does the risk of disease, social, and emotional problems. With an ACE score of four or more, things start getting serious.

“It is important to know, this it is not a life sentence, if you have ACEs. You can re-map the brain circuitry. There are things you can do like nutrition, exercise, stress reduction, meditation, and mindfulness,” assures Skala. “You do not have to live with the consequences of ACEs. If you know that, you can be more vigilant about things you need to do to be liberated. If you know about yourself, you can heal.

Improving Outcomes is Possible

The brain is not fixed and unchangeable, as was once thought, but can create new neural pathways to adapt to its needs. Scientists now know that the brain has an amazing ability to change and heal itself in response to mental experience. The human brain has the miraculous ability to reorganize itself by forming new connections between brain cells (neurons). Plasticity is the capacity of the brain to change with learning. New connections form and the internal structure of the existing synapses change. This phenomenon, known as neuroplasticity, is considered to be one of the most important developments in modern science for our understanding of the brain.

Building on the knowledge that the brain is plastic and the body wants to heal, this part of ACEs science includes evidence-based practice, as well as practice-based evidence by people, organizations and communities that are integrating trauma-informed and resilience-building practices. This ranges from looking at how the brain of a teen with a high ACE score can be healed with cognitive behavior therapy, to how schools can integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices that result in an increase in students’ scores, test grades and graduation rates.

While research shows that individuals who experienced ACEs are at greater risk of numerous ACE-associated health conditions, including nine of the 10 leading causes of death in the United States, we know that early detection, early intervention, and trauma-informed care can transform health outcomes.

"We really are in the infancy of ACEs and it is a very western-centric concept," observes Vestergaard. "We are now preparing the future medical workforce by including ACE awareness in the curriculum. Awareness is our best weapon to combat ACEs. Ultimately what we want is a prevention model, to teach how to build resiliency so that future generations can save money on health care costs and to save lives. That is why addressing ACEs now is so important."